New USU Study Suggests CTE Brain Disease Uncommon in Service Members

By Sarah Marshall

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy – also known as CTE – is a brain disease caused by repeated head trauma. There is still much to learn about this condition, however, it has commonly been thought of as a disease linked to contact sports, like football and boxing, and with military experience, such as blast exposure – that is, until now. A new study led by researchers at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) suggests CTE is actually uncommon in service members, and is more strongly linked to civilian traumatic brain injuries.

While it’s not yet understood how traumatic brain injuries contribute to the changes in the brain that result in CTE, it is believed that those with CTE develop a range of cognitive, behavioral, mood, and motor issues, later in life. Though it is well established that those who play contact sports, such as football and boxing are at a high risk for developing CTE, it’s also been commonly thought that service members are also at high risk. At this time, however, a CTE diagnosis can only be confirmed in an autopsy.

To better understand the frequency of CTE among service members, and to determine associations with various traumatic brain injury exposures, the USU researchers decided to embark on this study, published June 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine. They studied donated brains of 225 active duty and retired service members. They found only 10 of these individuals (4.4%) had traces of CTE – distinguished by a very distinct and recognizable pattern of pathology in the brain. Of those cases identified with CTE, half showed extremely minimal brain involvement, suggesting that CTE could not explain their symptomatology during life.

Also, just three out of 45 individuals in the blast-exposed group were found to have CTE. Of note, all of those who had CTE also had a history of participation in contact sports, most commonly football and combative sports, with or without an additional history of civilian head injuries unrelated to sports (e.g., car accidents). Ultimately, the researchers believe this suggests that the prevalence of CTE in the military community is rather low, and that the risk for CTE is numerically higher for civilian traumatic brain injuries.

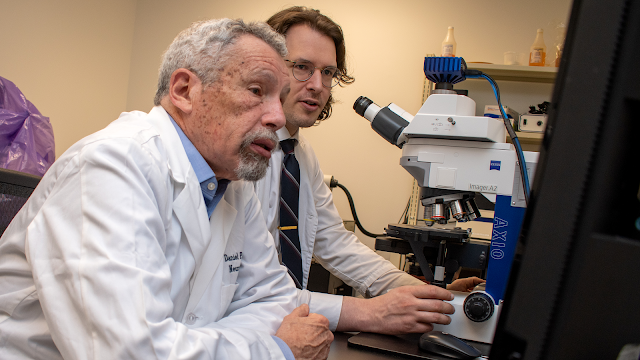

“We believe our findings provide some answers surrounding this condition and how it does, or does not, impact our service members,” said Dr. Dan Perl, who co-led the study and is a professor of Pathology at USU and director of the Department of Defense/USU collaborative Brain Tissue Repository.

In the specimens that the researchers examined, Perl added, many of the individuals were relatively young and had passed away only a few years after the time of their blast exposure. As service members exposed to blasts age, it may still be revealed that they become increasingly at risk for CTE from their exposures. However, these findings suggest that their risk might be significantly lower than previously thought.

“As our service members who have been exposed to blasts age, it remains possible that they may develop CTE or CTE-like pathology, though our study suggests that this may not occur,” said Dr. David Priemer, assistant professor of Pathology at USU, who also led the new study. “Regardless, our data indicate that CTE currently is not very common among service members and does not seem to be an underlying factor in the large majority of service members who suffer persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms following combat exposure.”

The DoD/USU Brain Tissue Repository continues to work towards better understanding the “invisible wound” of modern warfare and could not conduct such groundbreaking research without the precious gifts of brain donations from military families. The DoD/USU repository is also the only brain bank facility in the world that is exclusively dedicated to collecting, storing, and analyzing brains of individuals who have served in the military.

This study, “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in the Brains of Military Personnel,” was a collaboration between USU’s Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine and the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, and was funded by the Defense Health Agency.