Male Breast Cancer Is Rare, Real, and Dangerous: One USU Professor Speaks Out

By Sharon Holland

“Typical doctor, typical male.”

That’s how Dr. Norman M. Rich described his attitude when he first discovered a lump on his breast 10 years ago. Rich, a retired Army vascular surgeon and emeritus chair and professor of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences surgery department, simply ignored it. He had had lumps before and paid no attention to them.

However, when he later discovered a lump under his right arm, and noticed nipple retraction, he knew it might be an indication of a tumor and consulted his physician.

“Although I have spent years as a vascular surgeon, I remembered my general surgery training, and I knew it was not good. I called [Army Col.] Dr. Pat O’Malley, my primary physician, who thought I might have cancer of the breast. He referred me to Dr. Craig Shriver.”

|

| Dr. Norman Rich, professor and emeritus chair of the USU Department of Surgery, was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010. (USU Photo) |

Retired Army Col. (Dr.) Craig Shriver heads the Murtha Cancer Center at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and USU’s Murtha Cancer Center Research Program. Shriver ordered biopsies on the mass in Rich’s breast and under his arm, and both tested positive for breast cancer.

Breast cancer in men is rare. According to a 2020 report by the American Cancer Society, only about 2,600 cases of male breast cancer are diagnosed each year, compared to more than 276,000 in women. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of cases reported, and recognition that there are differences based on gender – men and women react differently to different treatments – but relatively few scientific studies. Rich says there are no significant benchmarks for breast cancer in men. As a result, all of his treatment options were based on those used for females.

"What should be obvious has no scientific basis,” said Rich.

“There has been a good amount of work and published studies done on male breast cancer since 2015. We are getting a better understanding of some of the differences between male and female breast cancer, specifically with regards to the genetics involved; therapeutic clinical trials for male breast cancer, specifically, are still lacking, however, due to low patient numbers for enrollment,” said Shriver.

In fact, the only two substantive studies on male breast cancer that Rich could find at the time of his diagnosis were from 2004 and 2007. In July 1, 2004, an article in the journal Cancer, “Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study,” by Giordano, et. al., showed the incidence of breast cancer in men was increasing. The study looked at data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results 1973-1998 Database, and showed an increase in breast cancer from .86 to 1.08 per every 100,000 men. Another study reported in Cancer in 2007, “Male breast cancer in the veterans affairs population: a comparative analysis,” by Nahleh, et. al., looked at male breast cancer in the Veterans Affairs (VA) population and also found the incidence was continuing to rise.

In the latter study, researchers used the VA’s Central Cancer Registry and looked at VA patients, both male and female, who had breast cancer diagnosed between 1995 and 2005. The study compared 612 male breast cancer patients with 2,413 female breast cancer patients and found that the average age for diagnosis in men was 67, while in women was 57. Black men were more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer and had a higher disease stage and more lymph node-positive disease. The study also found that men generally lived seven years after diagnosis, while women lived 9.8 years longer, although there were no statistically different survival rates for patients with stage II or stage IV disease. However, in stage I, survival rates in men were 6.1 years and 14.6 years for women.

Rich attributes the later diagnosis in men to denial. “Men tend to overlook the signs or discover it too late to address it,” he said. “It’s easy to deny and develop excuses for what you know it is.”

Or, it may be that men don’t know that it’s even possible to contract breast cancer or understand the risk, and relatively few are likely to conduct self-breast exams. But in fact, although they aren’t developed, men have milk ducts and their ductal system may be just as susceptible to breast cancer as a woman’s is; however, a diagnosis is often not sought or made until cancer has developed and spread into the lymph nodes, bones, or beyond. Men tend to develop larger tumors later in life, and more than 400 men are estimated by the American Cancer Society to die of breast cancer each year.

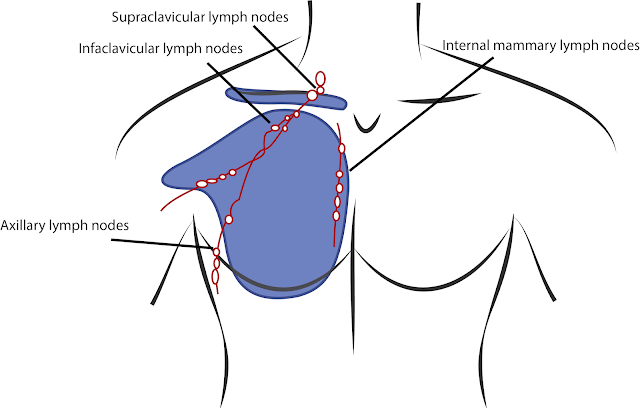

According to Rich, the tumor board at Walter Reed-Bethesda evaluates the treatment plans for all cancer patients at the hospital, and the board recommended he get a modified right radical mastectomy and lymph node dissection. Rich said six of his 37 axillary lymph nodes tested positive, so if the cancer was successfully removed, these procedures would be important for his longevity. The tumor board also recommended chemotherapy followed by radiation, followed by hormone therapy, although his medical oncologist told Rich that chemotherapy would only add two percent to his longevity.

“I can’t describe chemotherapy. Only people who have gone through chemotherapy can understand what it’s like,” Rich said, questioning why, for only a small return, anyone would subject themselves to the procedure. However, the oncologist told him it’s because it’s “part of the package deal.” Chemotherapy prepares the body for the radiation treatments, which prepare the body for the hormone therapy, and collectively they are the best opportunity for longevity – at least based on breast cancer studies in women.

In a discussion with Rich five years after his diagnosis, he reflected on his status. “I will never be cured since it had already spread [before diagnosis]. Will it come back? Yes. It’s more likely to in men. Women tend to pick it up early on mammograms. They can find a small, isolated area and test the sentinel node to see if it has spread or not.” Rich had a PET scan to detect whether it had spread to the bone and other areas and the results were negative. For those five years, he also took tamoxifen, which blocks estrogen receptors that lead to breast cancer.

“Studies in women say it prevents chest wall cancer recurrence,” he said. “Studies recommend that women take it for 10 years. It’s not a pleasant medication. It resulted in a 30-pound weight gain in six weeks that I couldn’t take off. It’s part of the price to pay to keep the cancer off the chest wall.”

But seven years into remission, his status changed. He was diagnosed with Stage IV breast cancer with metastasis to his spine, ribs and other bones. At Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Army Col. (Dr.) Melvin Helgesen performed surgery on Rich to stabilize his spine using steel rods in November 2019. Since then, his oncologist, retired Army Col. (Dr.) Jeremy Perkins has overseen his care.

“He [Perkins] has me on daily oral chemotherapy and infusion chemotherapy every three weeks. I spent nearly four months in Walter Reed and I am back in rehabilitation. I am essentially pain free and grateful for each and every additional day,” Rich said.

He isn’t quite sure how he developed breast cancer, but he has an idea.

“I had no family history of breast cancer. If there is a family history of women getting breast cancer, the men’s chances are increased. We didn’t have any and I went back five generations. No cancer anywhere. We took a family vote to see how everyone felt about me going through genetic testing, and everyone agreed I should do it. There were no mutations of BRCa1 or BRCa2 (which show an increased incidence of breast cancer in families). This may be political, but in Vietnam, I was exposed to Agent Orange. In 1965-’66, it was sprayed all over the highlands around me. No one was thinking about its potential toxic effects. I used to watch planes spewing it all over. I remember wiping it off my arms a few times,” said Rich. “In the VA system, there are so few cases of breast cancer, there aren’t any benchmarks. They have identified an increase in prostate cancer due to Agent Orange, but not breast cancer.”

Rich goes to the Murtha Cancer Center’s Breast Care Center on a regular basis for appointments. “It’s a superb organization and everyone is phenomenal,” he said. “I get a lot of stares from a lot of people, but it doesn’t bother me. Everyone is just surprised. They don’t think men can get it. This is a very important message for men. Everyone who gets a lump should get checked out right away. Early diagnosis and awareness is very important. Macho men have to put that attitude aside and recognize both women and men have breast tissue and can get cancer in the breast tissue.

“If you just walked out on the street, the vast majority would not know men could have cancer of the breast,” said Rich. “Being a physician and being concerned about health in general, if I’m able to alert a few more people and a few more people will get diagnosed as a result of sharing my story, it’s worth the effort.”

Maybe not so typical after all.