USU College of Allied Health Sciences Dean Says Perseverance is Key to Her Success

By Sharon Holland

Dr. Lula Pelayo chokes up when she talks about the motivation for her work with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences’ College of Allied Health Sciences.

“One of the reasons I am so dedicated to the College of Allied Health Sciences,” she says, with a catch in her voice, “has a lot to do with my husband, who was never able to capitalize on the training he received in the service. This is what the college is all about.”

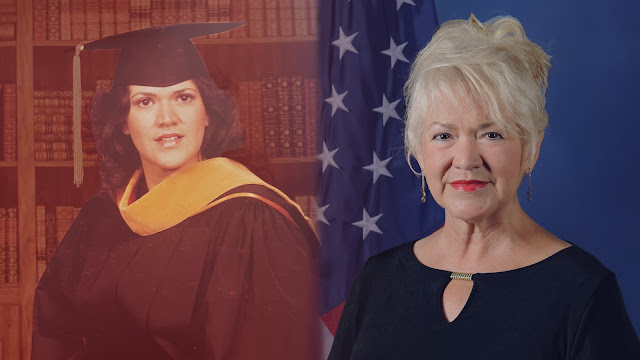

|

| Dr. Lula Pelayo leads the College of Allied Health Sciences as its dean. CAHS has more than 2,500 enlisted military service members currently enrolled. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Lula Pelayo) |

`“I was married when I was 18 as a senior in high school during the Vietnam era. My husband was sent to Vietnam and I didn’t see him for 13 months. During that time, I finished high school and began my college education. I was studying nursing and he had been in communications as a wireman. He dropped out of college when he volunteered for the Marine Corps, so he had some academic background but he had nothing towards a profession. He wanted to study something similar to what he was trained for in the services.”

But after she gave birth to their first child four years after they married, they decided only one of them could go to school while the other went to work to support the family.

“We couldn’t do both, so we just decided that he would be the one to go to work. I would go and finish my education since I was within two years of graduating with my bachelor’s degree in nursing, so I would have my profession. The plan was for him to eventually go back to school. Well, that didn’t happen.”

Fast forward several decades. By 2010, Pelayo, who was the first in her family to go to college, was district director of Nursing and Allied Health Programs for Alamo Colleges in San Antonio, Texas. She had risen from instructor to chairperson to dean and on to district director and was at the top of her field. That’s when she received a grant from the State of Texas that she used to establish the College Credit for Heroes program.

“I had always worked alongside corpsmen, medics, and 68 whiskeys [combat medics]. They would be working on my nursing unit and they were going back to school. They were learning how to take blood pressures, make beds…silly things that they were far more educated and trained for, but they could not get licensed. They couldn’t take the experience in the workplace that they’d learned in the service. Just like my husband was never able to take advantage of what he’d learned in the service and put it towards something. So, I developed an accelerated Associate degree in Nursing program for Army, Navy and Air Force medics and corpsmen. They could finish within one year after separating from the service and getting those courses instead of having to go the full two years plus two years of general education requirements.”

|

| Dr. Lula Pelayo was the first in her family to go to college, eventually rising to become dean of the College of Allied Health Sciences at USU. (Courtesy photo) |

“I eventually developed a military corpsman-to-nursing associate degree program. We developed several additional programs: military dental assisting-to-associate degree, military-to-respiratory therapy, military-to-occupational therapy, etc. I think I ended up with seven programs and they were all accelerated degree pathways. We would give our soldiers, sailors and veterans credit for the coursework they had taken in their training in the services. Because I had developed crosswalks, I was able to say ‘I’m not just going to consider you, or test you out, or see how well you do, I am going to give you direct credit for what’s documented on your JST [Joint Services Transcript].’ And I went back as far as seven years. So if they had completed training within seven years and they had a valid JST, we were able to take it. It’s still in existence today. It’s been very successful. If you notice around the country, there are many, many accelerated paths now. And I’m going to lay claim to fame because I think it began here in Texas,” Pelayo says.

The idea soon took root within the Department of Defense, and USU’s College of Allied Health Sciences was eventually established in April 2017.

“Now, [students] can achieve their degrees for their military training through the College of Allied Health Sciences or they can still partner with any private college or civilian college that they want. I’m very dedicated to what we do at the College of Allied Health Sciences and I believe that every facet of my education supports that.”

Pelayo holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing, a Master of Science degree in Nursing with a focus on curriculum and instruction, and a PhD in Nursing. She says she truly values the schooling she’s received as well as her profession – both nursing and education, and believes she was well prepared for her various roles in academia. And although she says that she knows what it’s like to be a dean, being the dean of CAHS “is a totally different animal.”

“The biggest struggle I’ve had, and that my predecessor had, was transmitting the message of who we are and what we are about to our own peers and colleagues. We don’t own the curriculum. The training and curriculum that we receive comes from the services. What they do is they contact us, and they say, ‘We would like you to consider this for placement in your catalog. Is there a program or a degree that can be had?’ So, we’ll conduct our evaluation and determine what it is that they want, the rigor in coursework, the outcomes, whether or not there’s sufficient training to establish residency, and the feasibility of bringing it on.” The bottom-line intent, Pelayo says, is to get recognizable, transcripted documentation that students can take with them and further their education.

Pelayo was initially hired to be the associate dean of Graduate Education for CAHS and, she says, she was the “civilian voice” for the military school. “You can imagine my learning curve in the last two and a half years. From zero to 150 mph – a real upward trajectory,” she says. But, Pelayo believes she has been able to provide “missing pieces” for the program. She also credits the CAHS staff for their knowledge and expertise and believes they work well as a team.

“Every day I marvel at the information that they have at their fingertips, and I often have the other pieces that help them frame it. Every day is a new experience. We’ve done a lot,” she continues. “It’s kind of rough, but it’s also exciting and I feel very productive at the end of the day. I think that’s the way all of our people feel. Everybody who is on board is committed to what we are doing for our service members.”

Pelayo says she is looking forward to the next steps for CAHS, including outcomes studies of graduates.

“We’re ready to take it to the next level. Once I get additional staff on board, I would like to be able to look back and see where we were, what we’ve done, and what the outcomes are – what are the results? What happens to our graduates? We have more than 1,000 graduates already. We now want to see what they’ve done and where they’re going.”

|

| Dr. Lula Pelayo has served as USU's CAHS dean since 2020. (Photo by Tom Balfour, USU) |

“You’re going to have roadblocks; expect them. Try and get help when you feel that you have a need. Don’t be hesitant to get that help. And then make a plan on how to follow through with it. It’s really easy to give up when you have obstacles. I can’t tell you how many times I wanted to give up, and I think that’s true of anyone. You give it what you can and you find it within yourself to keep moving forward. And sometimes there are times when you do have to turn around and take just a little bit of a different course. But I think it takes perseverance,” she says.

She also says her parents – particularly her mother – and her husband kept her on track and focused and were her strongest mentors, although she has had mentors within her profession along the way.

“Neither of my parents got past the fourth grade. My mother was born in Mexico, my father was born in the U.S. I remember how proud she was to get her naturalization as a U.S. citizen. Even though she was never formally educated, there was never a second thought that her children wouldn’t be afforded the opportunity. And although she couldn’t provide for me financially, she provided help for me and my family. She helped take care of my children. She made it possible for me to stay married, have children and go to school. She was there when I graduated and got my doctorate. She was a real smart woman. I would say she was brilliant. For someone with no formal education beyond the fourth grade, I relied on my mother's good, sound advice,” Pelayo says. “My second mentor would be my husband, through his support and his encouragement. The two of them are what made everything possible, and my two daughters have been the icing on the cake that kept me sane.”