Soldiers, Athletes Studied for Long-term Effects of Concussions

By Ian Neligh

West Point Graduate Army 1st Lt. Johnathan Cheatham received his head injury during the preliminary rounds of a brigade boxing tournament in 2015.

Cheatham was fighting a less experienced opponent and had him backed into a corner. They were given the command to “break”, or separate, and go into their respective corners when the incident occurred.

“I heard the command, stopped fighting, and turned towards my corner,” Cheatham says. “My opponent either did not hear, or chose not to listen, and punched me in the back of the head.”

When Cheatham woke, he found he had short-term memory loss and mood swings for about a week after the incident. It took a month before he was cleared for heavy exercise and two months before he could have contact in boxing again.

“It took about three months before I was back to normal. Recovery was every day working with an athletic trainer focusing on coordination,” says Cheatham, who is currently a basic training platoon leader. “Brain injuries are more common than people think, and prevention and treatment should be talked about just as much as all other injuries.”

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), or concussion, is a major issue of concern in the military, as well as within the sports community. The NCAA-DoD Grand Alliance CARE (Concussion Assessment, Research and Education) Consortium was established in 2014 to better understand sports-related concussions among varsity athletes. The consortium included universities and colleges across the U.S., including the four Military Service Academies: Army, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard.

Together, CARE and the Service Academy Longitudinal mTBI Outcomes Study (SALTOS) have successfully enrolled over 55,000 athletes, cadets and midshipmen from more than 30 U.S. campuses, with over 5,500 sustaining one or more concussions, making it the largest study of its type in history.

The initial part of the CARE study looked at the natural history, biomechanics, and neurobiology of acute concussion. The second phase, which is currently ongoing, looks at the intermediate effects of concussion and repetitive head impact over a college career. The third phase will investigate the long-term effects of concussions on members of the military and NCAA student-athletes.

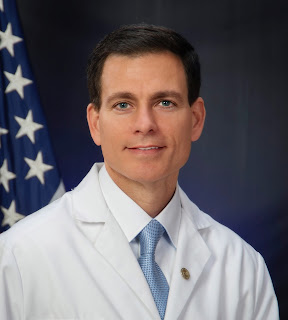

Pasquina, professor and chair of USU’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, describes the study as unique, in that it obtains a detailed baseline assessment of military service members and athletes, with near equal representation of men and women in both contact and non-contact sports. This allows the careful follow-up of those who sustain one or more concussions, as well as those who play contact sports, versus those who did not sustain a concussion or participate in contact sports.

“We’ve seen that approximately 20 percent of even the most highly motivated, highly fit, cognitively skilled, bright individuals will continue to have symptoms beyond 28 days after sustaining concussion,” Pasquina says. “This not only has implications for athletes, parents, coaches, and clinicians, but our military leaders, who often need to make decisions on when it is safe to return to sport, return to learn, or return to duty.”

Danielle Slack was separated as a cadet from West Point in 2017 because of the symptoms she received from a concussion during training. Slack says she was participating in an Advanced Combat Grappling course when she was injured fighting a larger opponent.

“I was elbowed in the head multiple times by a much larger man,” Slack says. “I lost vision multiple times in the fight but did not completely lose consciousness. I realized something was wrong when I had a splitting headache that lasted for hours. Instead of attending Taekwondo practice, I went to the concussion specialist for an evaluation and they confirmed I had a concussion.”

Slack says she dealt with severe headaches, light and noise sensitivity, inability to sleep more than two hours a night, irritability, and depression over six months.

Today she says she does not experience any significant symptoms that prevent her from functioning in her day-to-day life — but strongly believes the need exists for more awareness of the effects of concussions and proper treatment.

“People should understand the markers of healing, so they can assess their health and not feel the external pressure of deadlines to say that health is achieved,” Slack says.

According to Pasquina, the study is trying to inform the community not just that brain injuries are serious but that brain health is something the military is very invested in.

“Injury to the brain is something that all providers should be aware of and we hope that our medical students who are graduating from USU are all sensitive to the issues surrounding brain injury and brain health,” Pasquina says. He adds the same goes for those graduating from all of USU’s other graduate programs.

“We all need to be invested into what we, from our individual specialties, can contribute to the health and welfare of our military beneficiaries with regards to their brain health,” Pasquina says. “And that holds true whether you’re a physician, nurse, dentist, psychologist, therapist, dietitian, or a basic scientist.”

Army 1st Lt. James Manni is currently an operations officer for the United States Military Entrance Processing Command. The West Point graduate says he was injured in 2019 during a field training exercise.

“I was riding in a Bradley Fighting Vehicle when the driver lost control and took us through sand dunes at a high speed,” Manni says. “I knocked my head into the armor multiple times while wearing a helmet.”

He waited for treatment, which Manni says “was a huge mistake,” and was later diagnosed with a concussion.

“I underwent a few scans and MRIs to make sure there was no bleeding — but that is about it,” Manni says. “At that point, I was given a week profile from PT and sent back to my unit.”

But that wasn’t the end of the issue. Months later, he was still having headaches which grew worse. In time, Manni was diagnosed with trauma-induced migraines and still suffers from sleeping problems and some memory issues.

Pasquina says a cadet or midshipman may not be taking part in sports as a varsity athlete but they are absolutely participating in high-risk activities, such as combative training and in military training.

He says that every cadet and midshipman is at risk for potential brain injury so it only made sense to offer enrollment in the study to all cadets and midshipmen.

“As it turns out, the largest contributors to the data set have come from the service academies — primarily West Point and Air Force Academy,” Pasquina says. “A lot of information has been gathered by those baseline assessments and those concussive assessments on our service academy enrollees.”

Pasquina grew up playing contact sports and was a member of the varsity football team at West Point where he sustained a couple of concussions himself.

“Most memorably was when I got tackled and essentially woke up on the field with the coach, athletic trainer, and team doctor standing around me, I wondered, ‘what happened?’”

He remembers being helped back up, taking a few steps, then falling back to the ground.

“It was the most bizarre feeling that I’ve ever experienced, where I had no sense of where my legs were,” Pasquina says. “And I remember the trainer laughing along with me, saying 'you were knocked out.’”

Although he was removed from the game, he came back to practice the next day and a few days later was hit again. He described the entire stadium spinning, and although he did not lose consciousness, he immediately became concerned about his health and ability to ever play again. His coach and trainer reassured him that he just “got his bell rung” and advised him to try changing to a different helmet.

Pasquina now believes that he was lucky that since he played quarterback, he was able to avoid any direct head blows over the next few weeks and was able to complete his college career, but notes that, “fortunately, we recognize and treat concussion much differently today.”

“So I have a personal experience with concussion and loss of consciousness, and can very much relate to what my patients experience,” Pasquina says.

He says the best concussion treatment is early recognition, education, and protection of the brain while it is healing and then a gradual return to activities. Moreover, he explains the severe risks of brain injury or even death with “Second Impact Syndrome” if the brain sustains a second concussion before the symptoms of a first concussion have subsided.

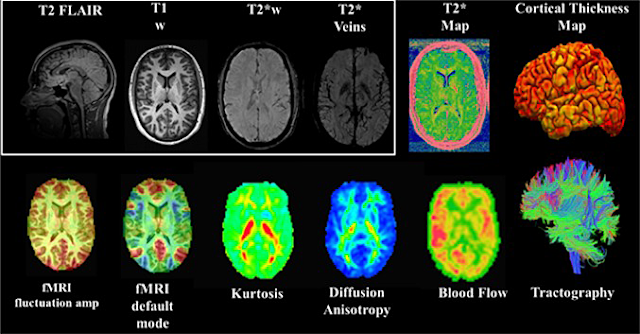

|

| CARE MRI integrating multimodal imaging biomarkers of changes in brain structure and function. Mild traumatic brain injury, or concussion, is a major issue of concern in the military, as well as within the sports community. The NCAA-DoD Grand Alliance CARE Consortium works to better understand sports-related concussions among varsity athletes including students at the four Military Service Academies. (Image courtesy of NCBI) |

According to Pasquina, the CARE/SALTOS consortium not only brings athletes, and military members together, but also a host of expert clinicians, scientists and researchers together under the umbrella of “team science,” where the large data repository can be queried with a multitude of hypotheses, which has resulted in nearly 100 peer-reviewed manuscripts, further advancing brain injury research.

“It’s a really rich database that allows us to look at trajectories of recovery for males versus females, individuals within the same sport or across sports,” Pasquina says. “Some factors may indicate a longer recovery versus a shorter recovery. What [is the average time to] return to unrestricted sports or return to learn?”

Additionally, Pasquina says during the next phase of study, USU is partnering with the Naval School Explosive Ordnance Disposal located at Eglin Air Force Base, Fla., to allow students and faculty at that school to enroll in the study, to better evaluate the military enlisted population, as well as the effect of blast exposure.

“It’s a very ambitious study, but USU is happy to partner with its military and civilian colleagues to help better understand brain injury and contribute to improved brain health,” Pasquina says.

He adds there’s no question that being a Soldier, Sailor, Airman, or Marine increases one’s risk of having a brain injury and is pretty much on par with playing a contact sport.

“This is a really important field and it is something that I’m very proud that USU had a leadership role in trying to answer unanswered questions — and to disseminate that knowledge as it becomes available to future leaders of military healthcare,” Pasquina says.