Women’s Health: Understanding Uterine Fibroids

By Vivian Mason

More than 70%-80% of women suffer from fibroids by the end of their reproductive years. Although it’s a common problem, most women don’t talk about it.

Fibroids are hormonally sensitive, benign (noncancerous) growths in the walls of the uterus. They can be as small as an apple seed or as big as a grapefruit and some can even be the size of a watermelon.

“Fibroids are an important health and military readiness concern,” says infertility specialist William Catherino, M.D., Ph.D.

Catherino, professor and director of the Research division in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU), has led fibroid research at USU for more than 16 years. Catherino is committed to exploring the mechanisms responsible for the cause of uterine fibroid development and growth in women. He’s also engaged in developing better and more effective treatment options for them.

“Fibroids are one of the leading reasons for surgery, whether it’s a hysterectomy or fibroid removal. Heavy menstrual bleeding, lower abdominal pain or pressure, and bladder leakage in women can disrupt their ability to deploy, thus attributing to reduced readiness. In addition, the male soldier with a dependent who is suffering from fibroids can have his readiness affected as well. Catherino’s research impacts a number of women who are not as military ready because of women’s health conditions,” said Air Force Colonel (Dr.) Barton Staat, associate professor and chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at USU.

According to the National Institutes of Health, more than 200,000 hysterectomies are performed per year as a course of treatment for uterine fibroids. Various studies show that fibroids are disproportionately more common in African American women. They are found to be more common, grow larger, are more severe, and occur at an earlier age in these women, although it is still not understood why this is true.

“African American women are three times more likely to develop fibroids than are Caucasian women,” said Catherino. He and several faculty researchers are looking at disparities in women’s healthcare regarding uterine fibroids affecting African American women.

When Catherino began his work 16 years ago, the only way to study human fibroids was to obtain surgical specimens and evaluate gene or protein expression at the time of surgery. However, over the years, he and his team have developed multiple in vitro and in vivo model systems to better study human fibroids. Using these models, they developed substantial insight and have continuing research into how fibroids form. He and his colleagues have also identified targets and mechanisms for current and novel therapies that could aid with individualized treatments.

Below are a few frequently asked questions about uterine fibroids that Catherino hopes will help others understand the condition.

What are uterine fibroids?

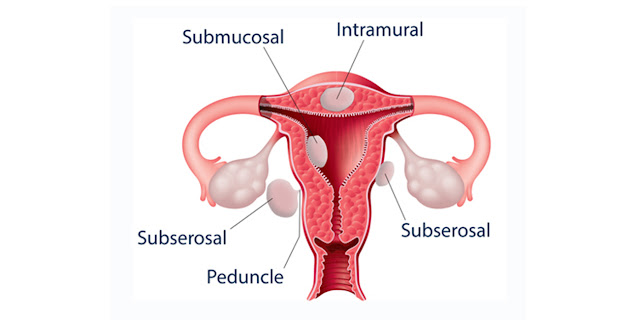

Uterine fibroids (also known as leiomyomas or myomas) are noncancerous tumors that are fairly common that grow in the wall of the uterus. They can vary in size, shape, number, and location. They can be submucosal (fibroids that grow inside the uterine cavity), intramural (fibroids that grow within the uterine wall), or subserosal (fibroids that grow on the outside of the uterus). Fibroids can seriously impact the lives of women as they deal with symptoms, surgeries, and recovery. Most notably, fibroids can play a major role in the ability of a woman to have a successful pregnancy.

What causes fibroids?

It isn’t exactly known what causes fibroids, although it is believed that hormonal and genetic factors could play a part. However, research has shown that certain factors can increase the risk of fibroids: age, race, family history, obesity, medicine, diet, early menstruation, etc. Current research has also revealed that the connective tissue made by the uterine fibroid cells is markedly abnormal. Thus, this abnormality may also contribute to the growth of fibroids.

Who gets fibroids?

Fibroids are most commonly detected in women ages 30 to 40 years old, but they can occur at any age during their reproductive years. Most women are unaware that they have fibroids until they are discovered during a routine pelvic exam. Fibroids occur more often in African American women than in Caucasian women. Studies show that fibroids tend to develop in African American women at a young age, and they also tend to develop more severe forms of the disease.

What are the symptoms of fibroids?

Not all women who have fibroids have symptoms. But women who do have symptoms often find fibroids difficult to live with, frequently dealing with pain and heavy menstrual bleeding. Symptoms can include the following: heavy or painful periods; changes in menstruation; bleeding between periods; pain in the lower back, abdomen, or during sex; frequent urination; feeling of fullness in the pelvic area; enlarged uterus and abdomen; miscarriage and pregnancy complications; and infertility.

How are fibroids diagnosed?

Often, a pelvic exam can detect the presence of fibroids. The following imaging tests can also be used: ultrasonography, MRI, CT scan, hysteroscopy, hysterosalpingography (detects abnormal changes in the uterus and fallopian tubes, but can only detect fibroids that are inside the uterus), sonohysterography (provides a clear picture of the uterine lining), and laparoscopy (looks inside the abdomen; doctor can see fibroids on the outside of the uterus).

How do you treat fibroids?

Treatment for uterine fibroids depends on the symptoms; however, current treatments are primarily surgical and interventional. If pregnancy is a future goal, then it can affect what treatment options are available. Catherino recommends talking with a gynecologist. Treating fibroids should be guided by the nature and severity of symptoms; desire for future fertility; age and health history; and the size, number, and location of the fibroids. Treatment can include the following: supportive care, medications, and devices surgery (either by myomectomy wherein the uterus is left in place or by hysterectomy wherein the uterus is removed—a hysterectomy is the only sure way to cure uterine fibroids; in the past, this was the standard for treating uterine fibroids); endometrial ablation (uterine lining removed); myolysis (electric current or freezing destroys fibroids); uterine artery embolization (blocks blood supply to fibroid and shrinks it; also a minimally invasive alternative to surgery); magnetic resonance imaging–guided ultrasound surgery (ultrasound destroys fibroids); radiofrequency ablation (shrinks fibroids); and antihormonal drugs.